UX Design Job & Career Growth Tips — Interview With Artiom Dashinsky

This is an interview based on a podcast episode featuring Artiom Dashinsky about his book, “Solving Product Design Exercises: Interview Questions & Answers”.

Harry: Welcome to “Breaking Backs,” the product book podcast, where I’m speaking to the authors themselves about their books, with the aim of finding out how these books can help you learn more, improve yourself, or even to make better products and services. Today, I'm going to be speaking to Artiom Dashinsky, the author of Solving Product Design Exercises.

What I really like about your book is the way it helps to think simply around difficult UX design interview challenges. It took me so many years in the industry to find out what to learn and then how to interview as a product designer within startups, and even in top tech firms and companies. If you are a designer looking for a job at the moment, or even maybe an internship within a startup or a big corporation, or even an agency, you should be buying and reading this book. I personally wish it was around 10 years ago when I was applying for roles, as it probably would have helped me get a few more of those jobs that I didn't get and wondered why I didn't get them.

Why I wrote this book

Harry: Artiom, can we just spend a minute to find out more about you, where you're from and maybe a bit about your past leading up to this point and writing Solving Product Design Exercises?

Artiom: Sure. I was born in Belarus following the breakup of the USSR and, when I was 16, I moved to Israel. And I think that was the biggest thing that impacted my future career because Israel is the second biggest startup hub in the world. It's in the third place after the US and China for the number of companies that are on NASDAQ. And it's a country of only nine million people. I believe it's first place in the world for the amount of venture capital invested per capita, and by the number of startups per capita.

So, as although it wasn’t my strategy when I was 16, when I moved there, I was lucky to be surrounded by innovation, tech companies and startups. During my career, I used to work as a designer in different formats — as a product designer, as a full-time employee, as a freelancer. I also had a small agency and product company. So, I held all types of positions as a designer and saw many different aspects of the industry by sitting on different chairs around the table, I would say.

One of the things that I kept seeing from the online design community, and also from my personal experience, is that designers working in tech are obsessed with visuals. It's something that we brought from graphic design because product design, UX design, UI design, digital design was all relatively new. And many people who got to these positions had a background in graphic design. So they were naturally focused on visuals and less aware of how their work is connected to the business side, how their work is helping the company to push forward its agenda, business objectives, vision, and how its work is measured.

Unfortunately, designers were often less aware of how their design work was helping the company. We can talk about reasons why we got to this point, but I believe that this situation is affecting the both sides: the companies and the designers. Because companies are not taking advantage of the full potential of designers, they are not letting designers move their business objectives forward. Designers, on the other side, don't really progress in their career. And they’re also struggling to understand what kinds of challenges they're supposed to be able to solve in order to work in top companies where a more business-oriented mindset is more appreciated.

Companies may struggle with the process of hiring designers too

Harry: I see a lot of friends now who are struggling with that, like myself. We started off as graphic designers, it was kind of a startup hub, and it was in the dot-com boom when it all started kicking off. As the years have gone on, it's much more focused on business and understanding your customers. But we still see 97% of startups failing now because they're not actually creating something that the customers need.

There's a bit in your book that talks around entry-level designers. They don't know what they aspire to do, what skills they should have or practice, and what kind of problems they're expected to solve to be hired by these top firms and companies. So, I remember going for a job interview probably about six or seven years ago in London; I went for about three or four all in a space of a week. And a lot of them just wanted pure visuals. But then some wanted their potential product designer to show them how to solve their business problems. It kind of stumped me at the time, as I was going for a pure design role.

To be honest, I think it was also kind of a mystery to them. They weren't sure what they were really asking for. They weren't asking for a particular thing. They were just asking, ‘how can you help us?’ And it was very open. So, I felt like there were a few years where startups and businesses went through this sort of big learning curve when it came to hiring designers: they didn't know what they really wanted or how to get a designer to do the job they actually needed. I felt like the digital world was obsessing over, I think you called it the ‘dribbblization of design,’ as opposed to what users actually needed.

Artiom: Yeah. I think that it's actually an issue that exists on both sides. The product designers aren’t sure what to expect when they go to an interview. And then they're not sure how to solve the testing exercises that they're given. But, also, the companies don't always know how to interview designers, especially in startups. In small startups, maybe this company is hiring their first designer. So there might be no one who has ever interviewed a designer. So, often, they don't really have a hiring process for designers, and they haven’t interviewed enough people yet to improve and optimize the process. In my book, I tried to create a type of a standard for both sides, a kind of mutual language that both designers and companies can use. This way they can test each other and understand if they want to work there or if the company wants to hire this person.

Why UX designers are overly focused on visuals

Artiom: I think that there are three reasons that led to this situation where designers are overly focused on the visuals and not giving enough attention to the business side of their work. You mentioned the Dribblization of design. We, as digital designers, started using design communities that are not created for product design. So, we started using Dribbble and Behance as places to show our work and to get inspired from others’ work. But these communities weren't originally created for UI design. As a result, it created the wrong perception of what product design is, both for employers and also for designers.

Harry: I really struggle to put anything on there now, I haven't used it for years. I remember when I was as a freelancer working for myself, it was fun and I could just put whatever up and it was how I got business. And now I struggle to do that because a lot of my job now is talking or working out the right things to actually do.

Artiom: Exactly. So, if you were an employer and you're trying to understand how to hire a designer, how do you know that the portfolio is good? You’ve heard of Dribbble, so you go there and you look at all of these visuals and you think that that's what you’re supposed to be looking for.

So, the second reason why designers are overly focused on visuals is that there's a lack of educational resources that are focused on things beyond visuals. The online courses don't have enough time to teach something that is beyond the craft, beyond the UI or UX design. And the design schools teach you all the basics of design, but they might not have enough capacity or enough knowledge to explain how such design works in the real world — what are the type of challenges you are supposed to be able to solve in order to work for Facebook, Google, or Amazon as a product designer?

And the third reason is lack of communication between businesses and the design community. The top companies like Facebook, Google, and Amazon can compete for the top 1% of talent. And this 1% of designers already have this “business” mindset. So, the companies don't have to share their case studies or internal processes in order to teach other designers. And unfortunately, because of that, a lot of junior designers don't really know what kind of things they should practice, what kind of things they should aspire for, and what kind of tasks they're expected to be able to solve in order to be hired by these top companies.

How I came up with my framework for solving product design interview challenges

Harry: Yeah. So, I personally like the framework that you've got in the book because I teach design sprints and, now, we're doing problem-framing, growth workshops. Every week, I'm doing a different type of workshop with different customers, wherever they need, and it’s great fun. I love doing it, and I work with companies in a variety of industries, from law to charities. So it's great to see that they're starting to use these more collaborative approaches of workshops and frameworks.

So, the framework for designers that you've got in your book is a really easy one to learn. The process is simple, and its one that creatives should be learning as it will help, not only with their job interviews, but also with workshops, facilitation and collaborative group skills.

Coming up with this framework, that's in your book. It's like a seven-step framework: the why, the who, where, what. I remember these because we do similar things within our company with problem framing, the four Ws. What experiences led you to start using this framework in particular? Was it because you had to hire more and more people? Or the standard of interview formats just weren't working for you and you decided to bring this sort of more creative approach to them?

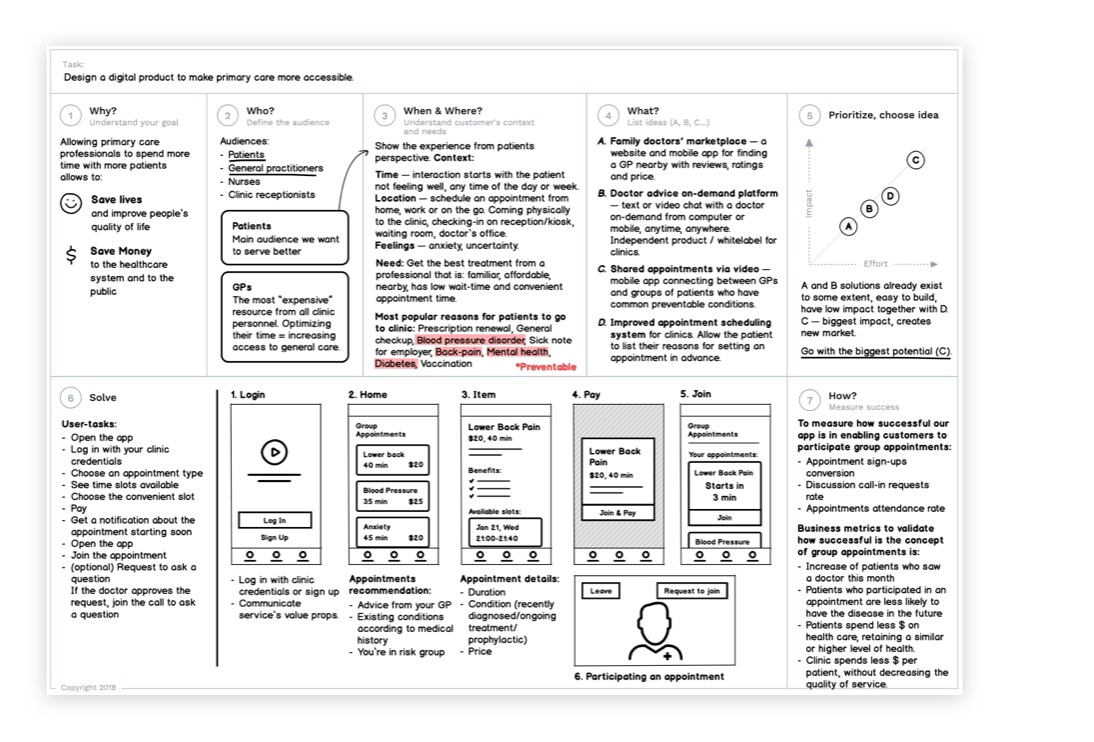

Artiom: I asked myself, how would I solve these exercises? How would companies expect to see them solved? So, I took real exercises that are used also by the company that I used to work for and also by companies like Google, Facebook, and so on. Then I just solved them myself. And I tried to find patterns and create a mutual structure for all of these answers. Then I read about different existing frameworks for problem solving to see if they could be useful. So, the “Five Ws and one H” you mentioned is a framework that is used also in police investigations, in journalism. This framework is helping to collect data and to do research. So, I thought that if it works for so many other areas, and it's very similar to how we as designers approach problems, it makes sense to use it partially in my framework as well.

So, basically, I solved real design exercises that are given to candidates during interviews and reverse engineered that process into a framework that anyone can use and anyone can apply to different exercises.

An important thing you want to show during design exercises is your process

Harry: Let’s say I'm in an interview, and I've been given one of the questions from your book, like creating a dashboard for freelancers or designing a kiosk interface. When we’re given such an exercise, we lack any real user insight. Are we okay to put that to the forefront and say, ‘what I'm going to create is a solution that doesn't have the customer context we'll need, and we need to validate the solution itself at the end of this.’

Artiom: Exactly. So, your job is to show your process. We spoke about Dribbblization of design, and most of us are indeed thinking visually. We tend to jump directly to the solution, to the wireframes, to the high-fidelity design. And this is one of the things that will set us up for failure, both in the real job and in the interview. So, an important thing you should remember when you're being interviewed is to show your thinking process and to show that you have a process and you are not just chaotically trying to come up with a solution.

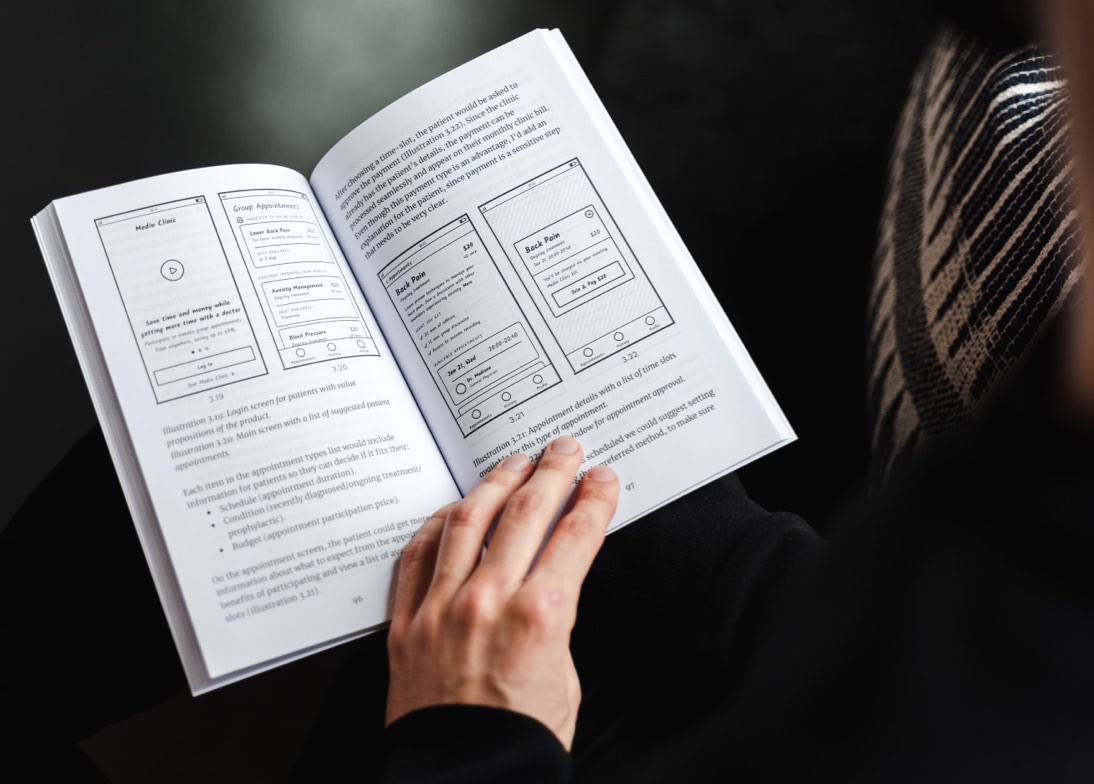

My framework includes different aspects of what you need to show in your answer: why you're building this, why this solution is good for the business and for the world, what is the audience that you're working with. You need to explain the user context and come up with several possible solutions, not just one; to show that you're aware of the different advantages and disadvantages of each solution that you are considering. You need to be able to prioritize each of them to understand which is having a bigger or lower impact, which will be easier or harder to develop, and then to try communicate all of this. So, basically, you need to fill out all of these empty spaces in your answer.

And often the question that you receive will actually have some of the answers to these questions. So, you mentioned this task of designing a dashboard for freelancers to manage their business. Here you already have the “who” — you already know who we are designing for: freelancers. Now, obviously you need to understand the type of freelancer so you can design a product that fits their needs. You have photographers or design and software developers. So, for example, photographers spend more time on the go, since their work is often happening in the field where they do their photoshoots. So, they they're more likely to use this product on their mobile phone. These types of contexts you need to understand. But, as I said, some of the questions will already have some of these answers; some of these pieces that you kind of fit together like a puzzle.

An interviewer wants to see not just your solution, but also how you collaborate

Harry: Following from there, no matter how experienced, I think some people are more nervous in interviews than others. So, if you get stuck during the process, I personally don't think you should be afraid of asking for more information. It is one thing that I've kind of learned during my time in different roles — in places I didn't ask for more detail, or I didn't quite understand, I didn't do so well in the job. So, some people can see this as a weakness and thinking and feeling like they're almost stupid, but I think we have to get out of that kind of head space and be open to asking.

Artiom: Yeah, totally. I think that it's also one of the things that people who are interviewing you want to see. They want to see the collaborative aspect, and it's also one of the reasons that testing exercises are given. They're not given just to see your solution. It’s important for them to see if you ask them the right questions, if you're making the right assumptions, if you're not afraid to involve people in the room, if you're good at explaining yourself and communicating, how you receive feedback. So, if somebody is giving you some pushback on your ideas and the direction that you're heading, how do you respond to that — are you getting defensive, or open to these types of remarks? At the end of the day, a design exercise might be not the perfect way to test every candidate, but it's the closest thing to the real job, considering the limited resources and time that companies have. And I think that during this process, it's very important to ask questions, as you said, and not to be afraid to involve people in your solution. The worst thing that will happen if you ask a question is the interviewer will say. “well, I don't know, but you can make an assumption on this, for example,” or “I don't know if it should be a purely digital product or also have from hardware involved, but you can decide that yourself.”

It's also important for companies to understand that, for people who are interviewed, it's not very easy to get in a room with other people that you just met and just start talking and presenting your work. They have to make sure that their candidates are comfortable, but they also need to be good partners in this type of exercise. They need to provide their assistance when the candidate feels that they're stuck and not to make them feel that they are trapped.

How the culture fit is tested during interviews

Harry: Within this interview process, where you are finding people out a bit and asking them questions to see how they react to you, do you also judge the culture fit? Or do you do that in a separate interview? For example, we almost get people in for a second interview to speak to others around the company. So, we pull different people in from around the company. And one of the good things we've got in our company is a really good culture. And I think it's very important for us to be able to keep that, you know; it's having similar sort of people and there's, there's nobody really that is an arsehole in our company, which is great.

Artiom: Yeah, exactly. So, it's one of the things that you obviously want to check; you want to check if they are the type of person that you will enjoy working with on a daily basis. It also depends on your definition of cultural fit. Normally it's something that every person who will interview the candidate, even beyond the design challenge, will try to check: if they are the type of person they can have a smooth communication with and feel that they will enjoy working with. My book is not really covering this aspect because I think that there are people who are much more experienced and knowledgeable in this aspect.

Harry: I think it's enthusiasm sometimes as well; if they're enthusiastic about what they're doing and it shows passion.

Artiom: Yeah. I think also that cultural differences are an interesting aspect of interviews. I used to interview mostly people in Israel, but I also interviewed Americans living in Israel. So, you can see very different approaches to interviews and what kind of things they're saying. I also at some point realized that I have this bias that if I'm interviewing someone who is a native English speaker, it always sounds like they are smarter because they're talking so well and just everything makes sense [laughs].

How to make your portfolios more appealing for businesses

Harry: How can people illustrate and show this problem-solving side in their portfolios? Have you seen any good examples of this and what sort of things they do?

Artiom: I went through a lot of portfolios, although I'm not an expert on building great portfolios. I’ll tell you what I wanted to see in portfolios as someone who was hiring designers to our team. First thing, as we said earlier — show that you have a process. Show your mindset of understanding how your work is affecting the business and how you measure your design. So, you want to position your work, not only in this kind of Dribbble-like way with sexy, aesthetically pleasing UI , but also to show the actual goal, what problem you tried to solve and how you helped the business to solve it. I think, ideally, businesses want to see you define a business-oriented problem. For example, “our goal was to increase our retention in the US market”; then show your solution through design, and the metrics that your design helped to change.

So, I think that this is something that many companies would be happy to see in portfolios. And I think that designers pay too much attention to the looks and how nice the animations are in their portfolios. I mean, I understand that very much, but as I move to the business side more and I'm building my own products, I understand how the aesthetic side is often given too much importance.

I also believe that the situation is getting better, by the way. I wrote my book two years ago, and I think that the situation has definitely got better since I wrote it. But it's still not perfect.

A secret design skill — being more like a product manager

Harry: I go to lots of conferences, and I’ve heard some really good talks lately about how, if companies have a better UX understanding across the board, from design to management to product managers, the product overall is going to be better.

What do you think a designer’s role is on that subject? How do you think a designer's role will evolve? So, in recent years we’ve seen things change dramatically; from when I first started a graphic design job 15 years ago, just coming up with things in Photoshop and banners and ads, it's become a lot more process driven and design-centric , allowing creative thinking to expand across the business more and more. But how do you think it will change as a job role in the coming years?

Artiom: In last two years, I've not been part of the design industry, but, how I see it, I think there is almost like a secret skill you can learn to become a much better designer — learn the skills of a product manager. So, all of these skills that we just mentioned in this business mindset — understanding how the design work is affecting the business metrics, how do we measure design etc — those are closer to the job of a product manager. I don't know if it's right or wrong, but I think one of the secrets to having a more successful design career is to learn more skills from product management: If you want to get a promotion, or you want to get a raise, or you want for people inside your organization to listen to your ideas. And that's one of the reasons that we see more product managers than designers become founders, I believe.

If you are closer to the decision making, you're closer to the business metrics, to the profits, to the money; your opinions, and your ability to influence, will be more significant inside the company. This way you are more likely to get a promotion or a raise. And I think that it's one of the things that designers could implement relatively painlessly to accelerate their career growth.

Harry: I agree 100% with all of that. I think designers are becoming more like product managers as well. I feel like learning just simple things like the framework in your book really helps you up-skill as a junior or mid-level designer now.

Artiom: Yeah, and it took both of us some years of our career to understand that. And now designers can learn from us to have this shortcut; to consider being more involved in business decisions to become more successful in your career.

Although it also may be something that you do not enjoy. That's a different issue, so obviously you need to decide: maybe you actually enjoy just designing highly aesthetic visuals. But then you cannot really complain that you're not being heard on product decisions.

Reducing chances of getting stuck while solving UX challenges

Harry: What would you give as a tip for junior designers to give them the confidence to go for one of these interviews?

Artiom: If you're afraid that you will get stuck during the design challenge and you will forget the steps in your process, you can start your presentation by explicitly outlining it and saying ‘this is what I’m going to do next’ and explain the steps of your process. You can even write down on the whiteboard the steps that you're going through — defining the audience, their context, determining how this product is affecting the business, etc. It will help you to remember the steps, and it also will help you show the interviewer that you following a process, even if you get stuck or forget a certain step.

Harry: Brilliant. So, thanks so much for joining me today, Artiom, it was really great speaking with you about your book. Solving Product Design Exercises: Interview Questions & Answers is available online. You can also get a video course. This is my second copy of your book. I think I gave the first one away to someone I was doing a workshop with. Thank you for speaking to me today, Artiom.